UA investigates fertility risks from common chemicals

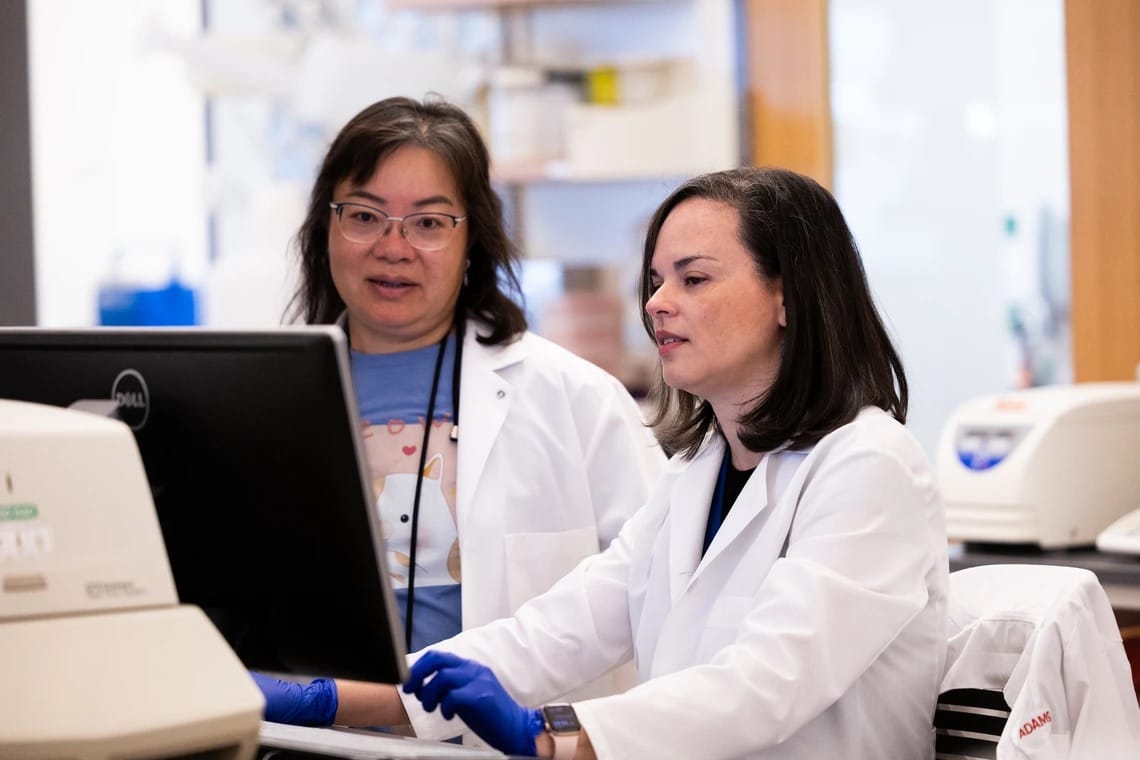

University of Arizona researchers are studying how everyday chemicals, including phthalates, may disrupt hormones and affect women’s fertility.

Scientists at the University of Arizona are tracing how chemicals we encounter every day, from plastics to personal care products, may interfere with hormones and quietly chip away at women’s fertility.

The work is supported by a $2.8 million award from the National Institutes of Health to expand understanding of how phthalates affect reproductive health.

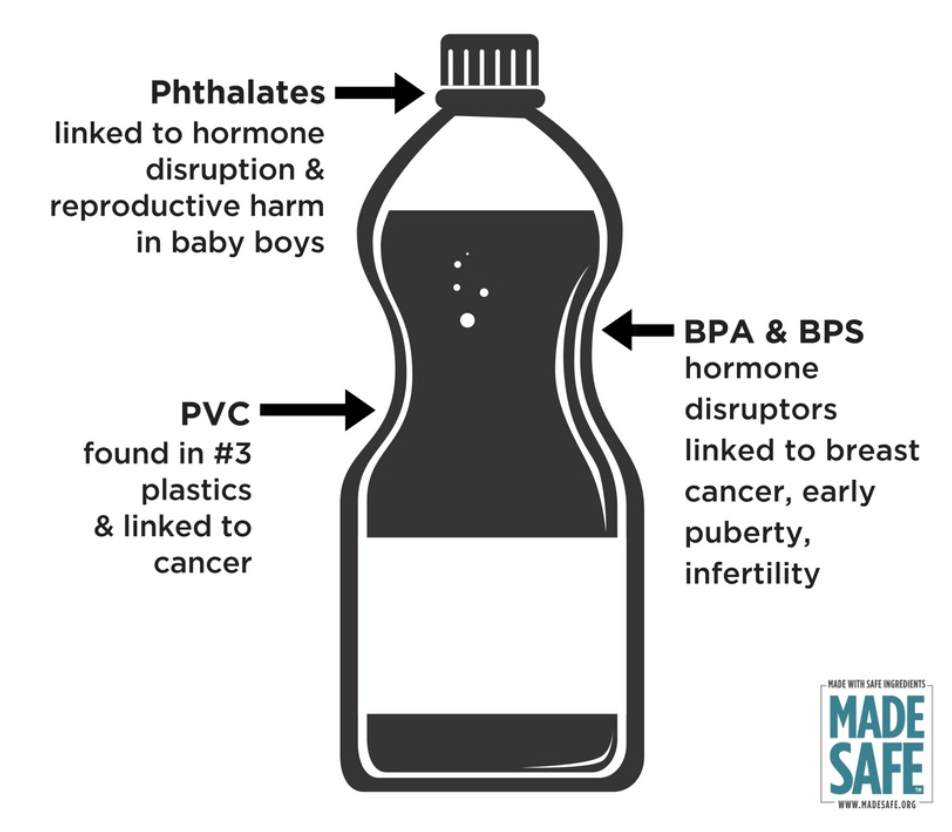

Phthalates are chemicals used to make plastics flexible, but they can easily leach into water, soil and air.

“They can also be used in other substances, for example, beauty products, they can also be used in personal hygiene products,” Zelieann Craig, associate professor and assistant dean of research at the UA’s School of Animal and Comparative Biomedical Sciences, told Tucson Spotlight.

Craig is a toxicologist and an expert in ovarian function whose research focuses on understanding how environmental exposures to chemicals released from wildfires influence reproductive health.

Her interests in hormones and the reproductive system trace back to her undergraduate days at the University of Puerto Rico.

“I learned that it’s not just genetics or aging that can affect your ability to have babies,” she said. “There are also things in the environment like chemicals that we’re exposed to in our daily lives through water, air and our jobs.”

Phthalates can disrupt the endocrine system, a network of glands that produce and release hormones into the body.

Craig referenced a 2011 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that measured the amount of phthalates in urine among men and women.

“Women tended to have higher levels of specific phthalates than men or children,” she said. “That really triggered the idea that we definitely need to look at them closer.”

She said phthalate and other chemical exposures can lead to reduced egg production by the ovaries or miscarriage.

“We don’t have information on things that are directly causing this, but it just so happens that the same patient that these things are happening to, they also find that they have higher levels of phthalates in their urine,” she said.

Craig said her lab has found that phthalates can affect the proteins the body uses to regulate how fats and hormones—known as lipids—are processed.

“It is very interesting to see that, because phthalates have been shown to be associated with metabolic syndrome and in some cases, obesity,” she said. “In our work we have found that it's doing similar things.”

Craig added that in ovarian cells, an impaired ability to process lipids can contribute to conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome.

“We really want to know what is consistently happening and what are the different cell types and different proteins that are involved in this to make sure we can understand how to prevent it or how to reverse it,” she said.

Craig’s research is part of the College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences’ broader portfolio, which supports hundreds of projects totaling more than $99 million in annual research activity.

"Dr. Craig’s research addresses a growing need for us to better understand the impacts of trace organic chemicals on women’s health,” said Interim Associate Vice President of Research Jon Chorover. “Many such chemicals, and phthalates in particular, are encountered in a wide variety of personal care products that are sold over the counter.”

Craig said this grant will help take her research to the next level while continuing to offer teaching and research opportunities to students.

“These new grants are going to help us go into more detail so that we can really identify what are the processes at the alert level that are being affected by phthalates,” she said.

To reduce phthalate exposure, Craig recommends using fewer plastics and fragranced products and choosing items labeled “phthalate-free.” Beyond phthalates, Craig’s lab will continue to study how chemicals from wildfires affect women’s fertility.

“It’s very important to have not only healthy babies, but also healthy mothers that can take care of them,” Craig said.

Arilynn Hyatt is a journalism major at the University of Arizona and Tucson Spotlight intern. Contact her at arilynndhyatt@arizona.edu.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please consider supporting our work with a tax-deductible donation.