Tucson rescues see growing need for tortoise adopters

Wildlife officials say adoption needs are rising statewide as captive desert tortoises, including Tucson resident Kathy Weir’s beloved Sherman, require long-term, secure homes to survive.

Across Arizona, wildlife officials say the need for tortoise adopters has never been greater, and Tucson resident Kathy Weir has seen firsthand how permanent homes can change the fate of the state’s captive desert tortoises.

Weir grew up with a passion for turtles and tortoises, visiting Indigenous markets and eyeing pottery and crafts in search of anything that symbolized two of Earth’s oldest living reptiles.

But her fondness for the creatures isn’t limited to art.

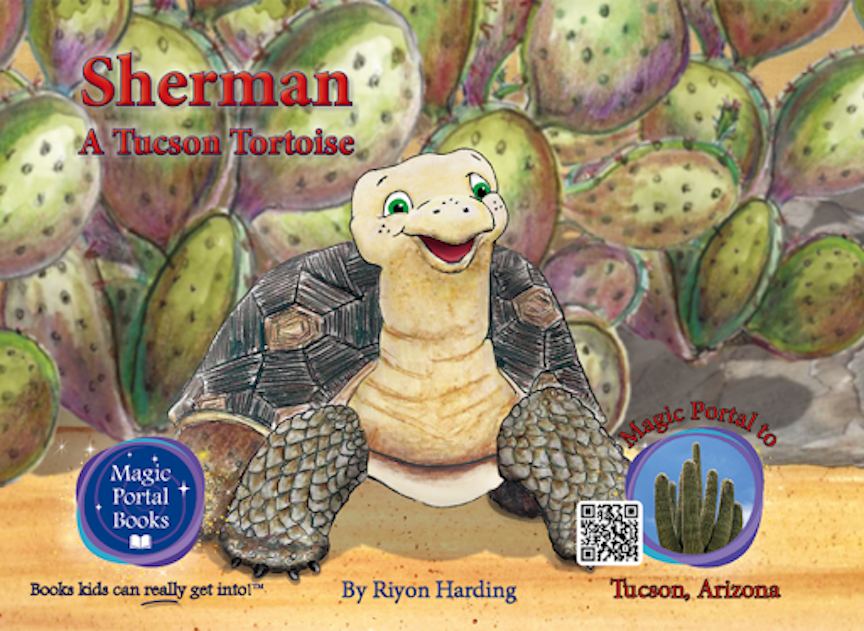

Weir, 77, raised a Sonoran Desert tortoise, Sherman, who became a celebrity after a Tucson author wrote a book about him to help educate children on the Sonoran Desert’s wildlife and ecosystem.

In the book, Sherman explores Tucson with his fellow desert animal friends, teaching children about the desert ecosystem, history and geology.

Weir adopted Sherman in the early 2000s as a newborn, caring for him for 15 years before having to find a new home for him in order to care for her husband.

But he didn’t go far: Weir’s next-door neighbors ended up taking him in, thanks to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum’s adoption program.

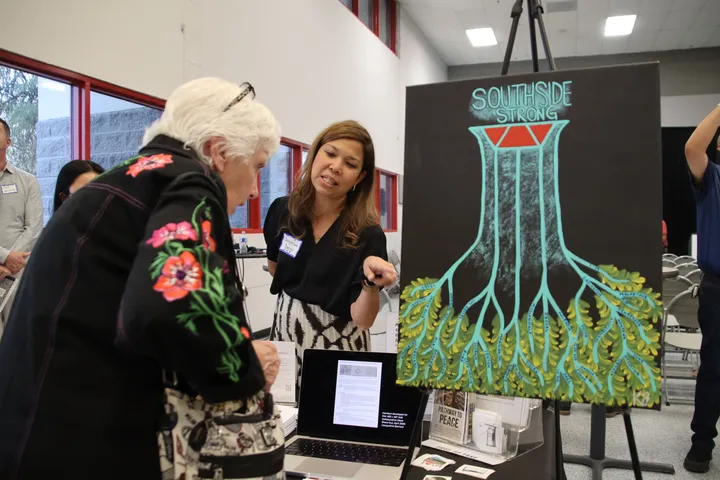

The museum’s adoption program is one of several in the state that help find homes for captive desert tortoises.

Help us unlock our $10,000 donor match and support the next generation of Tucson journalists.

Without a permanent shelter, captive reptiles returned to the wilderness can’t survive on their own. With hundreds of desert tortoises taken in by Arizona Game and Fish each year, the need for adoption is increasing.

Tortoise adoption programs gave Weir a companion while also securing a home for Sherman.

One of Sherman’s adopters, Riyon Harding, is founder of Magic Portal Books. After adopting the tortoise, she wrote “Sherman: A Tucson Tortoise.”

“I figured his destiny was to become famous,” Weir said.

Arizona Game and Fish spokesman Michael Colaianni said the department is looking year-round for animal lovers willing to adopt a tortoise.

Game and Fish takes in hundreds of desert tortoises each year, since once they’ve been captured, they can no longer live in the wild. The reptiles, native to both the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, are often illegally bred in captivity and therefore highly susceptible to disease if released.

Respiratory infections like mycoplasma are a huge problem because they are very contagious, said Game and Fish intern Sophia Langran.

“If they were to have mycoplasma and be released to the wild, then they could affect every population, and that would multiply and spread across Arizona,” she said.

Other dangers for wild desert tortoises include drought, wildfires, cars and invasive plant species.

“When they are in captivity for long periods of time, they kind of lose their natural instincts,” Langran said.

On average, 150 to 200 desert tortoises from Arizona are adopted out annually by the department. During the 2025 fiscal year, 153 were adopted, with forever homes for the reptiles always in need.

Caretakers are required to have an enclosure of at least 120 square feet with a perimeter fence 18 inches high and 8 inches deep. The reptiles must also have access to sun and shade throughout the day and an above-ground burrow with a minimum of 8 inches of soil on the top and sides.

There can be no pools, toxic plants or chemical treatments near their habitat.

Caretakers also need to provide native grasses or wildflowers for food and constant access to water.

Game and Fish advises adopters to have a long-term plan for the animal’s care, as healthy tortoises can live 80 to 100 years and may outlive their caretakers.

When Weir could no longer care for Sherman, she gave him to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum to be adopted into a safe home.

She fondly remembers her time with Sherman and how he seemed to hear her each morning when she stepped outside to pick up her newspaper.

“By the time I walked back and came through the gate, it was like he came out and gave me the eye like, ‘Where’s my breakfast?’” Weir said. “And then I’d go into the house and give him some lettuce or whatever I had that I was going to share with him that day.”

Trevor Gribble is a journalism major at the University of Arizona and Tucson Spotlight intern. Contact him at tjgribble@arizona.edu.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please consider supporting our work with a tax-deductible donation.