Tucson providers push for better mental health access

As Arizona continues to rank among the worst states for mental health access, Tucson providers are working to expand care through local partnerships, telehealth, and student-led initiatives.

A new study shows Arizona’s mental health system ranks near the bottom nationally, but in Tucson, local providers are working to close gaps in access and strengthen care.

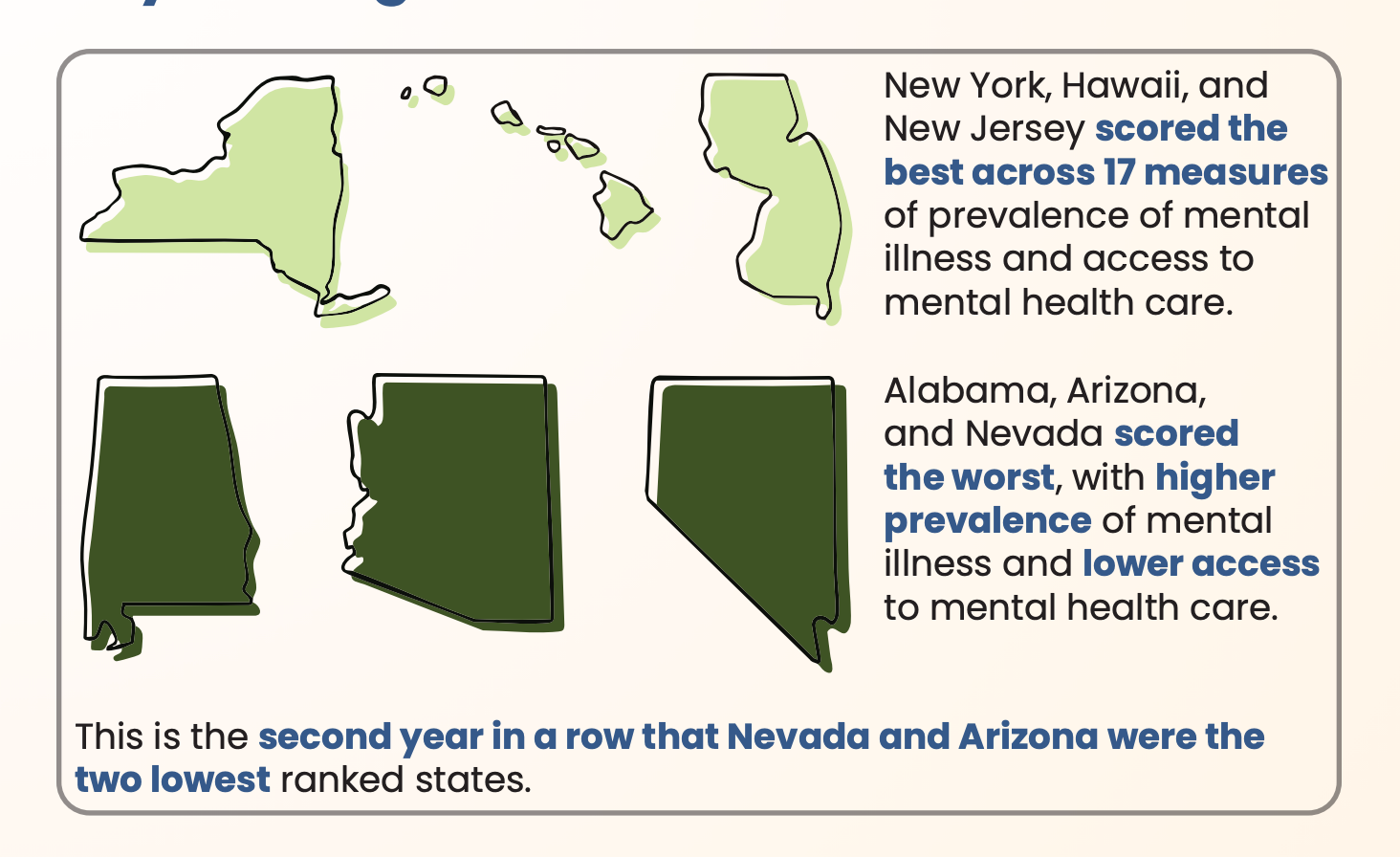

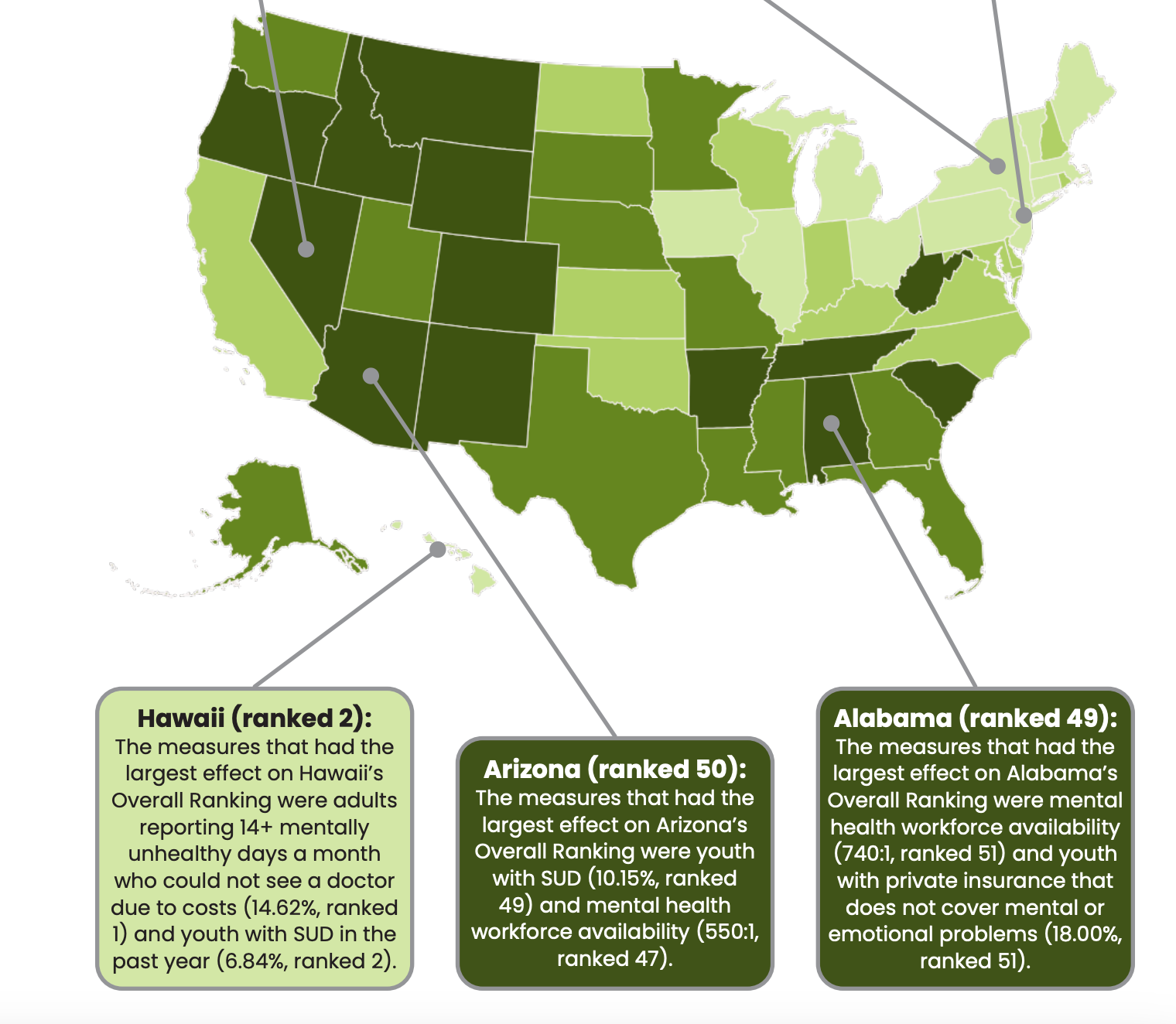

Mental Health America’s latest report placed Arizona 50th out of 51 states and the District of Columbia for access to and quality of care, citing high rates of mental illness combined with limited access to treatment, insurance coverage gaps and a thin mental-health workforce.

This is the second report in a row where Arizona ranks in the bottom two. Local experts, including leaders at CODAC Health, Recovery and Wellness and the University of Arizona’s Counseling and Psychological Services, say the shortage of psychiatrists, therapists and affordable care in Southern Arizona highlights how statewide underfunding and workforce gaps continue to strain communities.

The report analyzed states based on 17 factors, including mental illness, substance use disorder, suicidal ideation, and access to and coverage of care.

Mental health providers across the state say the ranking reflects long-standing challenges.

“Arizona's challenges sort of mirror those national trends, but Arizona certainly amplifies these trends because, based on geography, and also, we have a lot of rural and tribal communities within the state of Arizona,” said Dr. Amy Muñoz, chief compliance officer at CODAC .

Muñoz said Arizona’s low ranking is largely due to its rural geography.

She pointed to Bisbee, which has only a few practicing psychiatrists.

Psychology Today lists two in-person psychiatrists in the area, while U.S. News & World Report lists three others and links to online care options for Bisbee residents.

Distance and transportation are common barriers in many parts of the state, she said, adding that many providers are exploring solutions to meet clients where they are.

“Our low ranking is not a reflection of the commitment of the providers, the healthcare professionals in the community, but certainly indicative of larger, systemic challenges,” Muñoz said.

And despite Tucson’s urban setting, Muñoz said it mirrors national issues including workforce shortages and a lack of specialized care.

“We certainly feel it on a microscale here in Tucson — lack of psychiatry, lack of nurse practitioners, lack of licensed therapists, specifically in underserved regions,” she said. “Additionally, there’s high turnover due to burnout, and we just aren’t able to reimburse these folks for the work that they do.”

She said CODAC also focuses on reaching Tucson’s unhoused population and recently received a grant to support its partnership with local hospitals.

“We're partnering with emergency departments to try to assist folks there where we might anticipate them presenting first,” Muñoz said.

Much of CODAC’s recent work has focused on policy efforts to expand access to care, increase Medicaid reimbursement rates and simplify billing.

Muñoz noted that Arizona has historically faced criticism over fraud, waste and abuse within its mental health programs. Fraudulent billing by the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System has cost taxpayers at least $2 billion and disproportionately affected Indigenous communities, according to the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting.

As a result, CODAC is working to rebuild public trust.

We're "advocating for providers that weren't part of that so that they aren't inadvertently punished because of some issues that occurred previously,” Muñoz said.

Work is also being done at the university level to help improve access to mental health care for students.

Dr. Aaron Barnes, director of Counseling and Psychological Services at the University of Arizona, said many students have faced challenges accessing care, noting that it’s often harder for people unfamiliar with the mental health system to find help in a college setting.

“If people aren't connecting with therapy or with mental health resources at a time where they're growing up in high school, if they're not used to the idea of accessing care, that might serve as a barrier, or just a lack of education about what mental health treatment looks like by the time they enroll at the University of Arizona,” Barnes said.

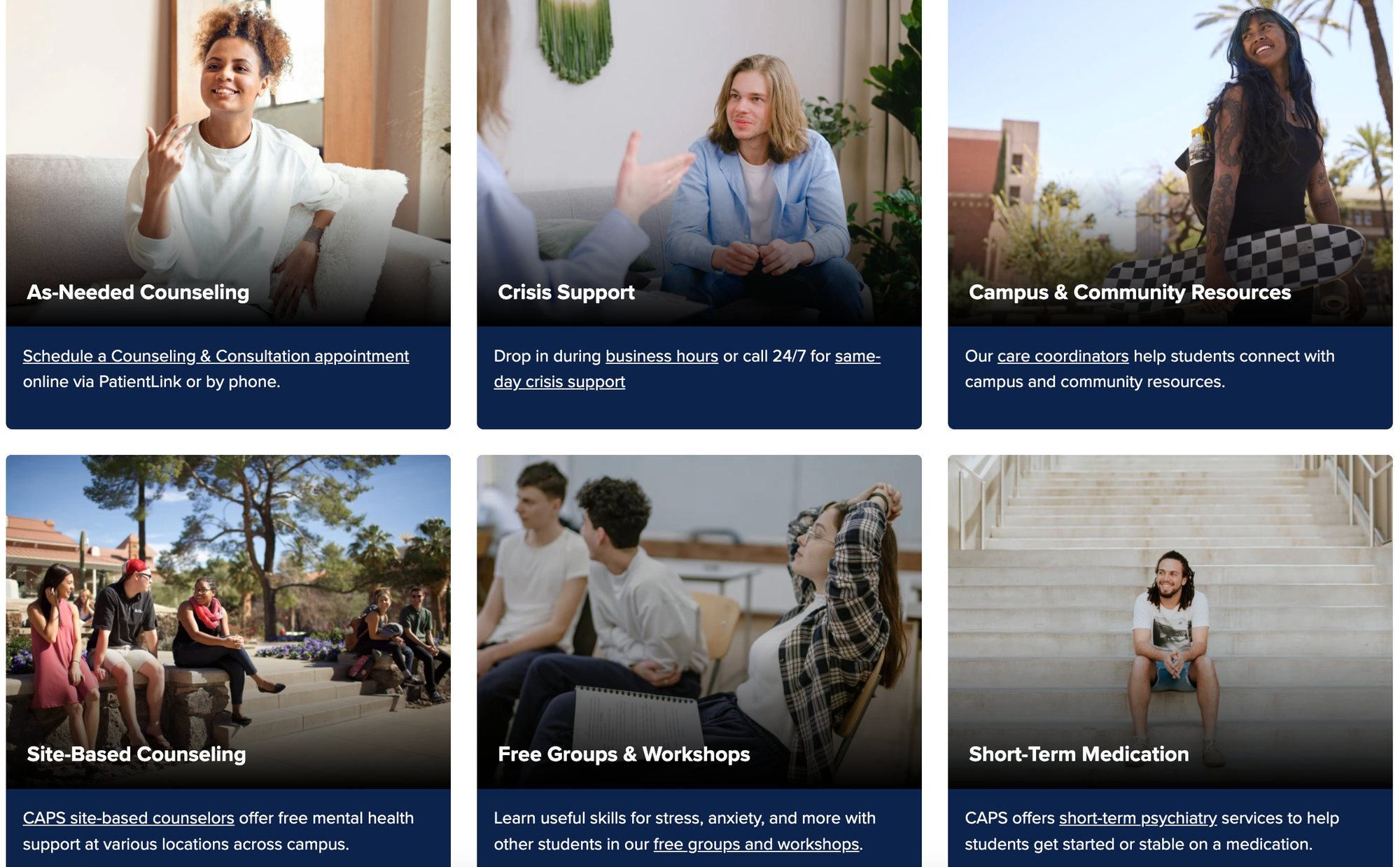

CAPS operates independently from the state health care system and focuses on evidence-based practices for students. The center is dedicated to ensuring that every student and faculty member is informed about available resources.

One initiative to improve access is Well Cats, a group of student ambassadors from Campus Health who help peers navigate care.

Barnes described CAPS’ approach as “stepped care,” meaning finding the best way to match the right type of care to each person.

“We try to make it easy, sort of intuitive, for students to move up and down that level of care, whether that means they just passively see us tabling on the mall, or if they need psychiatric or crisis care in the clinic,” Barnes said.

He also said CAPS has worked to eliminate another barrier: communication.

“We kind of make fun of young people sometimes in our society for not talking on the phone. But I'm like, ‘If I could do a text box or a chat or schedule online, 1,000% I'm always going to do it that way,’” Barnes said. “Online scheduling helped remove a barrier for a lot of students — many of whom have never even made a medical appointment for themselves.”

CAPS has also embedded counselors in spaces like the LGBTQ+ Resource Center and the College of Medicine to make care more visible.

“The idea is those students will see those counselors’ faces in the places that they are,” Barnes said. “They'll hear from their fellow students, like, ‘Oh, I went to see so-and-so, and they were great. They helped me with XYZ.’”

Barnes said university campuses are often the best place for students to receive psychiatric care, as traveling off campus can bring barriers like cost and long wait times — issues less common at the university level, especially for students with UA health insurance.

While Barnes’ current efforts include destigmatizing psychiatry among professors, he said the best way students can support one another is to talk openly about their mental health experiences.

For Barnes, the state’s low ranking underscores why universities must lead by example in reshaping access to care.

"There’s the Arizona behavioral health stuff going on, and certainly the mental health rating is relevant, but we built this system independently of all of that,” Barnes said. "We just do what we think works for students, and we study it and we do more of that.”

Emma LaPointe is a journalism, political science and German Studies major at the University of Arizona and Tucson Spotlight intern. Contact her at emma.m.lapointe@gmail.com.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please consider supporting our work with a tax-deductible donation.