Tucson experts call for disaster-level response to extreme heat

Local experts say treating extreme heat like a natural disaster—with coordinated responses and increased public awareness—is key to protecting Arizonans as temperatures rise.

Local experts say the key to surviving extreme heat may be treating it like a natural disaster — by naming heat waves, training a heat-informed workforce and unifying emergency responses across the state.

That idea, among others, emerged during a "Living with Extreme Heat" seminar hosted last month hosted by the Community Foundation for Southern Arizona, where public health experts and climate advocates shared new strategies for protecting Arizonans as triple-digit temperatures become the norm.

“Anyone who’s lived through a summer here in Southern Arizona or anywhere in Arizona knows heat is more than just an inconvenience,” said Community Foundation President and CEO Jenny Flynn.

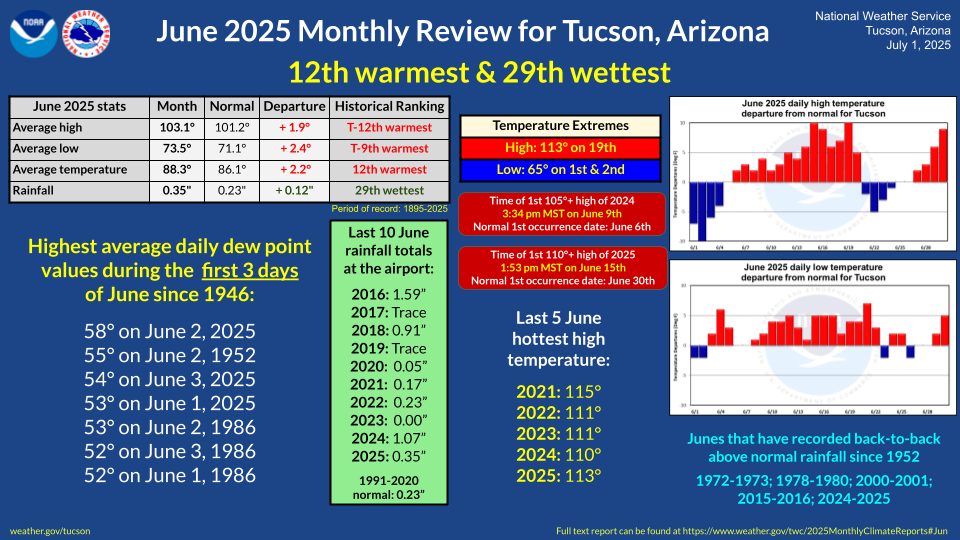

In June, Tucson’s temperatures were 2.2 degrees above normal, with 23 days of a high of 100 degrees or more. The average daily temperature was 103.1 degrees, according to the National Weather Service.

“Extreme heat kills more people each year than any other weather-related phenomenon in the United States,” said Nate Young, program manager for the Pima County Health Department’s Office of Heat Response and Relief.

The health department established the office to spread information on heat-related illnesses, cooling centers and other resources. Young said one of the most urgent heat-related issues is awareness.

“I think there are just a lot of ways where we can increase public perception and awareness of the issue and kind of get more people involved in heat response,” he said.

Extreme heat can cause short-term health effects like heat exhaustion and heat stroke, as well as long-term conditions such as chronic kidney disease. Young said long-term health risks are generally tied to people who are consistently exposed to extreme heat or lack proper hydration.

“They may not be aware of it for several years, and then when they do become aware of it, it’s already progressed to a pretty advanced stage where they may be having to immediately start dialysis,” he said.

This all stems from the heat island effect that has taken over Tucson, according to Joaquin Murrieta-Saldivar, cultural ecologist director for the Watershed Management Group.

The heat island effect is a phenomenon where cities become significantly warmer than surrounding rural areas due to an abundance of heat-absorbing surfaces like concrete and pavement, which trap and retain heat.

“We are creating tremendous high temperatures for people indoors and outdoors and as well for nature, wildlife and plants,” Murrieta-Saldivar said.

Arizona is emerging as a national leader in extreme heat response, and panelists emphasized that there are many ways to address the growing risks posed by rising temperatures.

“A heat-ready and a heat-informed workforce is really important to build out right now,” said Maren Mahoney, director of the Office of Resiliency at the Arizona governor’s office.

When Gov. Katie Hobbs took office in 2023, Arizona experienced its hottest summer on record. Mahoney said the governor’s office recognized the need to strengthen its response to extreme heat.

One way the office has strengthened its response is through ongoing communication with municipalities — including Tucson, Phoenix and Tempe — and county governments. Hobbs also created the state’s first Chief Heat Officer position.

With more resources and growing awareness of heat risks, the state has developed a heat risk tier system to ensure a coordinated response among municipalities, nonprofits and counties.

“I think that was a really innovative solution that the state came up with in the wake of the development of our extreme heat preparedness plan,” Mahoney said.

Pima County’s Young pointed to the La Isla Network as another example of efforts to spread awareness. The nonprofit began looking into sugarcane workers and heat illnesses in Nicaragua after workers started dying in their early 20s and 30s due to continuous heat exposure.

“For people who are continuously exposed, the long-term impacts may not always be apparent until it’s kind of too late for them,” he said.

Panelists also discussed the idea of naming extreme heat events, similar to how the World Meteorological Organization names tropical storms and hurricanes, as a way to raise awareness and convey the severity of heat risks.

They discussed using solar panels to help offset energy costs driven by rising heat, with Murrieta-Saldivar suggesting that Tucson create designated microclimates — areas within the city with distinct weather conditions — to help cool the environment.

“Creating conditions for microclimates to develop more transpiration because that’s what is diminishing the temperatures in the environment,” he said.

By leveraging Mayor Regina Romero’s Million Tree Initiative to plant more trees across Tucson and creating rain gardens — shallow depressions that collect and absorb rainwater runoff from roofs, sidewalks and other surfaces — the city can begin to cool down, Murrieta-Saldivar said.

“We know that increased vegetation brings down ambient temperature, and that there’s often a correlation between communities that are higher income,” said Murrieta, noting the disparity in Tucson’s shade canopy.

Changing behaviors like driving less and working from home can also help cool the city.

As temperatures continue to rise and triple-digit days become more frequent, Tucson continues to address its response collectively.

“We’re listening to our local community and we’re trying to find solutions that not only keep people safe, but are also meeting their needs as well,” Young said.

Arilynn Hyatt is a journalism major at the University of Arizona and Tucson Spotlight intern. Contact her at arilynndhyatt@arizona.edu.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please consider supporting our work with a tax-deductible donation.