Students say Native history lacks present context

Students at three Arizona high schools say their Native American history classes focus mainly on past events and do not fully address contemporary Indigenous communities and issues.

Several students in Sierra Vista, Tombstone, and Sahuarita high schools say their Native American history lessons focus primarily on early events like the establishment and forced occupations of reservations, with little coverage of contemporary Indigenous issues.

Many reported that if they relied solely on their school education, they would be unaware that Native peoples and their tribal nations continue to exist today.

The accounts come from students at rural schools in Pima and Cochise counties and do not represent instruction in Tucson-area districts or Phoenix schools.

Arizona law includes several statutes — A.R.S. 15-244, 15-341.33, and 15-710 — that aim to support schools in delivering culturally relevant and standards-aligned Native American history.

The Arizona State Board of Education also emphasizes integrating Native languages, culture and history into school curricula, and the Office of Indian Education holds annual summits promoting cultural wellness and policy development.

Despite these efforts, the five students who spoke with Tucson Spotlight say the information they receive does not reflect current realities faced by Indigenous communities.

Multiple requests by Tucson Spotlight to speak with Tombstone Unified School District Superintendent Sarah Cox and Sierra Vista Unified School School District Interim Superintendent Terri Romo went unanswered.

SVUSD policy prohibits teachers and staff from speaking with members of the media.

Eighteen-year-old William Sporhase, who is one-eighth Apache and attends Tombstone High School, said socioeconomic lessons were limited.

“Just that they have casinos now and that is how they make their money,” he said. “I was not aware that not all of them have casinos.”

Sporhase recalls learning more about his heritage through his half-Apache grandfather and personal study.

Walter Adkinson, 18, a student at Buena High School in Sierra Vista, compared his current school’s instruction to the more in-depth Diné language classes he took while living in Flagstaff.

Buena “understood what (Native Americans) went through and the challenges they faced, according to what I know,” Adkinson.

But he said the “few weeks” spent on Native history lacked coverage of contemporary socioeconomic issues.

“The (Indian Removal Act of 1862) was framed as a compromise since they didn’t want to assimilate,” Addison Russell, 18, said of the Native education she received at Buena.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 is a federal law that authorized the forced relocation of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands to territories west of the Mississippi River. Some states passed related laws later, such as Arizona’s version in 1862, which continued similar policies.

Meanwhile, Haylee Steward, 18, from Sahuarita High School, recalled only that “alcohol was a problem” in relation to modern tribal nation issues, with no further context provided.

Other recent seniors and graduates said they were unaware of current events or conditions on reservations. Other than Sporhase, the other students interviewed reported feeling some guilt or negative emotions while learning about Native history.

They all agreed that teaching this history is important to help prevent the repetition of past injustices and expressed a desire to learn more about Indigenous issues today. Sporhase added that the information presented in high school was similar to what he learned in elementary school, just with more detail.

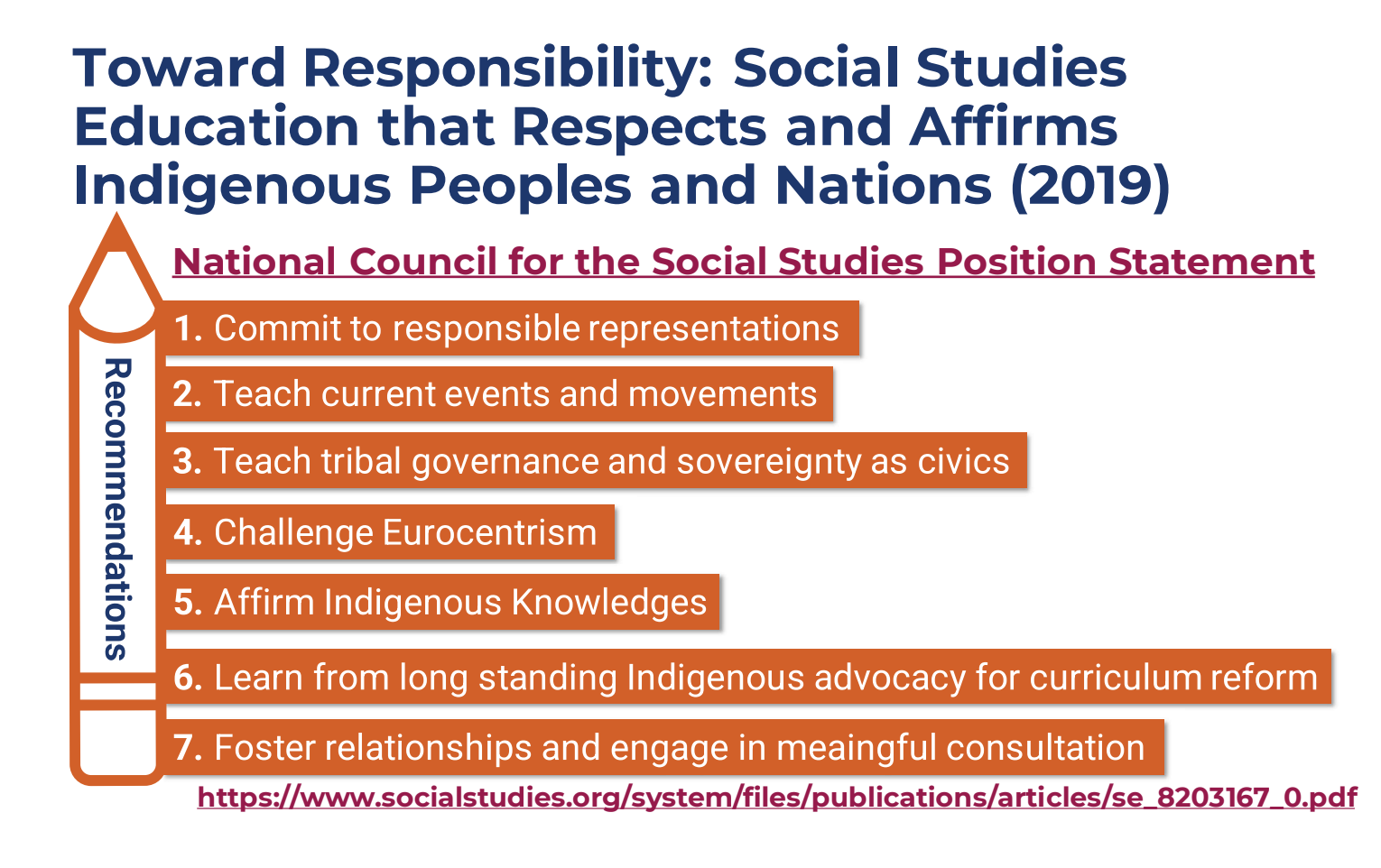

A 2024 Office of Indian Education summit presentation highlighted a journal from The National Council for the Social Studies emphasizing responsible representation of Indigenous peoples in education.

The journal called for teaching current events, sovereignty as civics and affirming Indigenous knowledge to support both Native and non-Native students. It warns that generalizing all tribes into one narrative is as harmful as ignoring Indigenous history altogether.

“Misrepresentations harm Indigenous students, negatively impacting their self-esteem, while at the same time giving non-Indigenous students a ‘psychological boost’ and false sense of superiority,” the journal said. “This is exacerbated by media such as films and mascots that reinforce narrow stereotypes.”

Adkinson said Buena presented its Native studies curriculum in a similar way.

Students said their curriculum mainly covered historical U.S.–tribal interactions but does not extend to explain the ongoing consequences of that history.

In 2022, state lawmakers introduced House Bill 2561, which would have expanded instruction on tribal history, culture, sovereignty, treaty rights, government, socioeconomic experiences and current events.

The bill mandated that starting in the 2024-25 school year, academic standards include instruction on the Native American experience in Arizona that is historically accurate, culturally relevant, community-based, contemporary and developmentally appropriate.

The bill made it through a second reading in the House, but did not progress further.

The Arizona State Board of Education supports integrating Native American languages, cultures, and histories into all areas of the curriculum to foster mutual understanding between American Indian and non-Indian populations.

Without confirmation of what is being taught, it is unclear whether the gaps students describe stem from the curriculum itself or how it is delivered.

What is clear, they say, is a desire to learn more about Indigenous history and the realities facing tribal communities in Arizona today.

Katherine Martinez is a a Kickapoo-Potawatomi Native majoring in journalism at the University of Arizona and Tucson Spotlight intern. Contact her at martinezk29@arizona.edu.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please consider supporting our work with a tax-deductible donation.