South Tucson residents navigate a “Food Prison” after grocery closure

The closure of South Tucson’s only full-service grocery store has intensified safety concerns and deepened long-standing inequities as residents and advocates push for solutions.

Months after South Tucson’s only full-service grocery store closed, residents are still struggling with the loss of their closest source of fresh and affordable food. Community organizers say the closure highlights longstanding systemic inequities tied to environmental racism and decades of disinvestment in the small desert city.

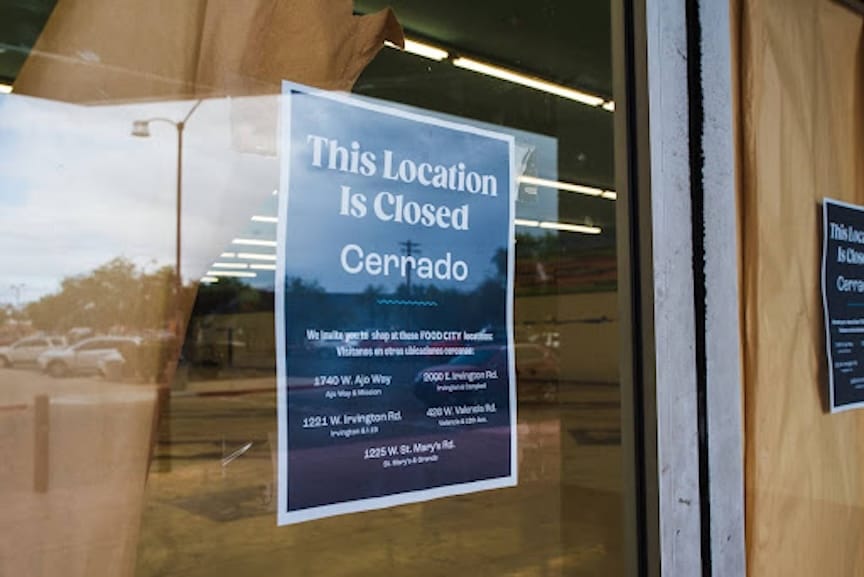

Food City, previously located at 2950 S. 6th Ave., permanently closed its doors Oct. 3.

The closure means an extended trip to the nearest supermarket, the El Super on South 6th Avenue. For residents without a car, the pedestrian route has raised safety concerns among many, including South Tucson Vice Mayor Melissa Brown-Dominguez.

Brown-Dominguez said residents now face a longer, more risky trip.

"There is El Super across the bridge, but some residents have told me they don't feel safe there, so they don't use the (bus) stop,” she told Tucson Spotlight. “To get to Walmart from here, they can't just go down Park (Avenue,) they have to go downtown and get on another bus line. For the elderly and disabled, as well as families, that can be hard to navigate.”

Support bilingual, community-centered reporting and double your impact through our donor match

The city has a handful of independent markets and stores, but the prices are much higher, Brown-Dominguez said.

“That's not a fault of theirs, since you can't compete with big box stores,” she said.

Nelda Ruiz, a community and cultural organizer from Nogales who has been working to promote food justice in Tucson and surrounding communities since the early 2000s, shared a similar concern.

“Folks in a wheelchair, in a walker, in crutches it’s very unsafe to get there,” she said. “Removing the only option that was available for the community here is only going to exacerbate the barriers in being able to obtain affordable, culturally relevant foods.”

Ruiz has been working to educate the community about food access and insecurity in South Tucson and beyond for years.

“I do several workshops on food deserts here in Tucson, and the reason (is) because our community organizing work here in the south side is all about the intersections of food justice and environmental racism,” she said. “The topic, unfortunately, is one that I'm very familiar and versed with.”

A food desert is defined as a community or population that lives more than 1 mile away from a supermarket or a large grocery store, according to the USDA.

Now that Food City is gone, the nearest supermarket, El Super at 3372 S. 6th Ave., is 1.7 miles from South Tucson City Hall at 1601 S. 6th Ave.

Brown-Dominguez is working to remedy the situation, saying she hopes a new grocer will move into the vacant Food City building and fill the gap.

“There are many layers of difficulties to do that," Brown-Dominguez said. "One, it is an expensive space to lease, and it's hard to get any big store to come into our area, because they look at the demographics and medium income, and ours is low here. It's not really my responsibility because it is a privately owned space, but if I can advocate and facilitate a conversation, I want to do it.”

Ruiz said she sees food deserts as part of a much larger systemic issue that at times targets marginalized communities.

“We don't refer to them as food deserts because our options for food choices are designed that way. We refer to them as food prisons because it reframes it as systemic and intentional, and it points to the structures of confinement and control that restrict people's choices, especially in low-income and racialized communities,” she said. “Calling it a desert often time hides the policies, the zoning, the corporate consolidation, and the disinvestment that created the problem in the first place.”

Without a permanent solution to make food access more equitable through policy changes or community investment, South Tucson falls into a deficit, according to Ruiz, who said she’ll continue her efforts to amplify the effects of food justice.

Ruiz said because it's a systemic issue, it's not coincidental that things are the way they are. She said that because of this, the importance of promoting equity and questioning the possibilities of the world is vital.

“How are incentives given for culturally relevant food retail? How are residents involved in shaping the food system?” she asked. “It just invites us to think beyond like a grocery store.”

Ease of access to food becomes even more complicated, Ruiz said, when organizations working to address the problem — including Garden Kitchen, South Tucson Community Outreach and Casa Maria — all rely on the same source.

“To somebody who's not involved in the food systems work here in the region, (it) looks like there's a lot of options to choose from, that community members have a long list of resources to choose where to access food,” she said. “But the truth of the matter is that the hub, like where all the food is coming from, is one place, and that's the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona.”

Despite the struggles residents of South Tucson now face, advocates insist the small desert city is resilient.

“Most narratives about south side communities across the country are those of like deficit and blight, and a community that is so needed,” she said. “We know that those truths are real. We live them every day, but I also think it's important to point toward the resilience and the strategies underway.”

Freelance journalist Colton Allder contributed to this story.

Nya Belcastro is a University of Arizona student and Tucson Spotlight intern. Contact her at nya2005@arizona.edu.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please consider supporting our work with a tax-deductible donation.