Reentry simulation exposes barriers for Tucson participants

A reentry simulation gave participants a firsthand look at how missing IDs, limited transportation and strict supervision can derail the lives of people returning from incarceration.

It took only a few minutes inside a reentry simulation at the YWCA of Southern Arizona for participants to feel the pressure formerly incarcerated people face daily, as simple tasks like buying food or attending probation became obstacles stacked against them.

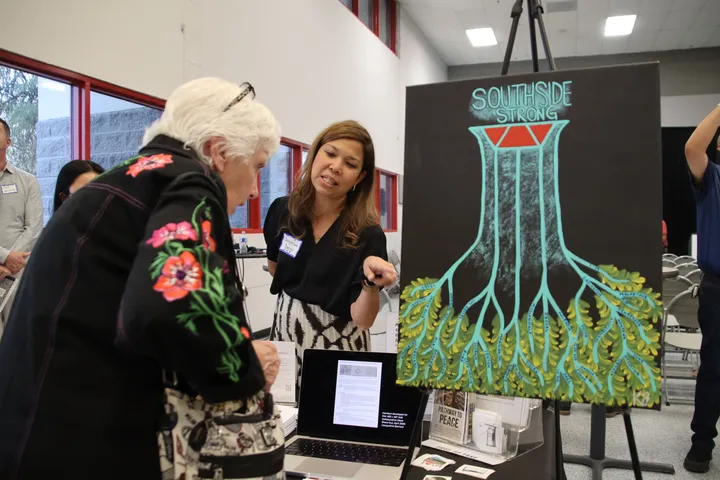

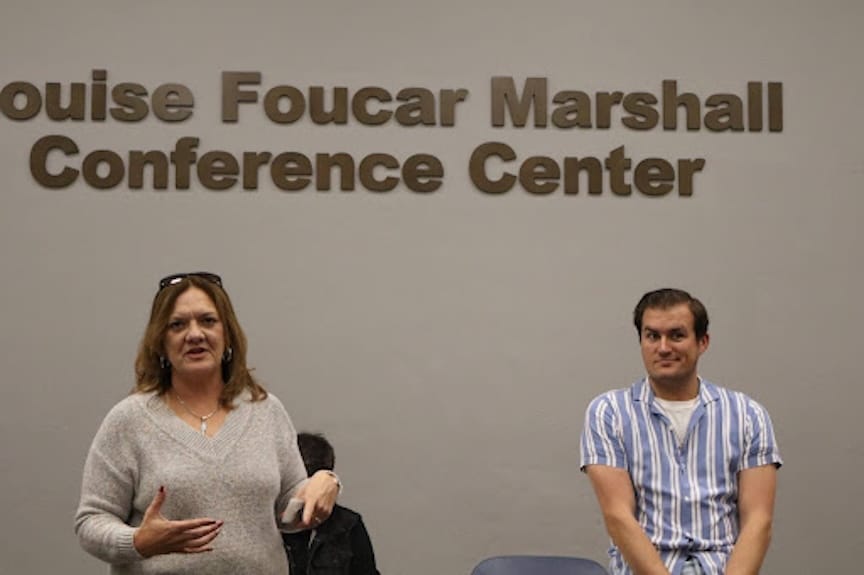

The event was sponsored by Dr. Laura Banks Reed Center for Gender & Racial Equity via the McArthur Foundation Safety & Justice Challenge. Phoenix’s Arouet Foundation facilitated the event to give Tucsonans a chance to spend a month walking in the shoes of someone reentering society after spending time in prison or jail.

The nonprofit specializes in helping women with reentry and connecting them with resources like employment and financial services in order to build a solid life foundation. It says formerly incarcerated women who partake in at least three of their services have a recidivism rate of 2% over three years, compared with the state average of 36%.

Despite having 13 state prison facilities, the Arizona state prison system includes only one women’s prison, Perryville, located near Goodyear.

Arouet’s programs start within Perryville, but participants have to reach out after their release in order to receive help with things like benefits access or mentorships.

“If you’ve been caught doing the worst thing you’ve done on your worst day, you very, very much are likely to be caught up in the same cycle that the people in the simulation are,” said Arouet community affairs director Grant Packwood.

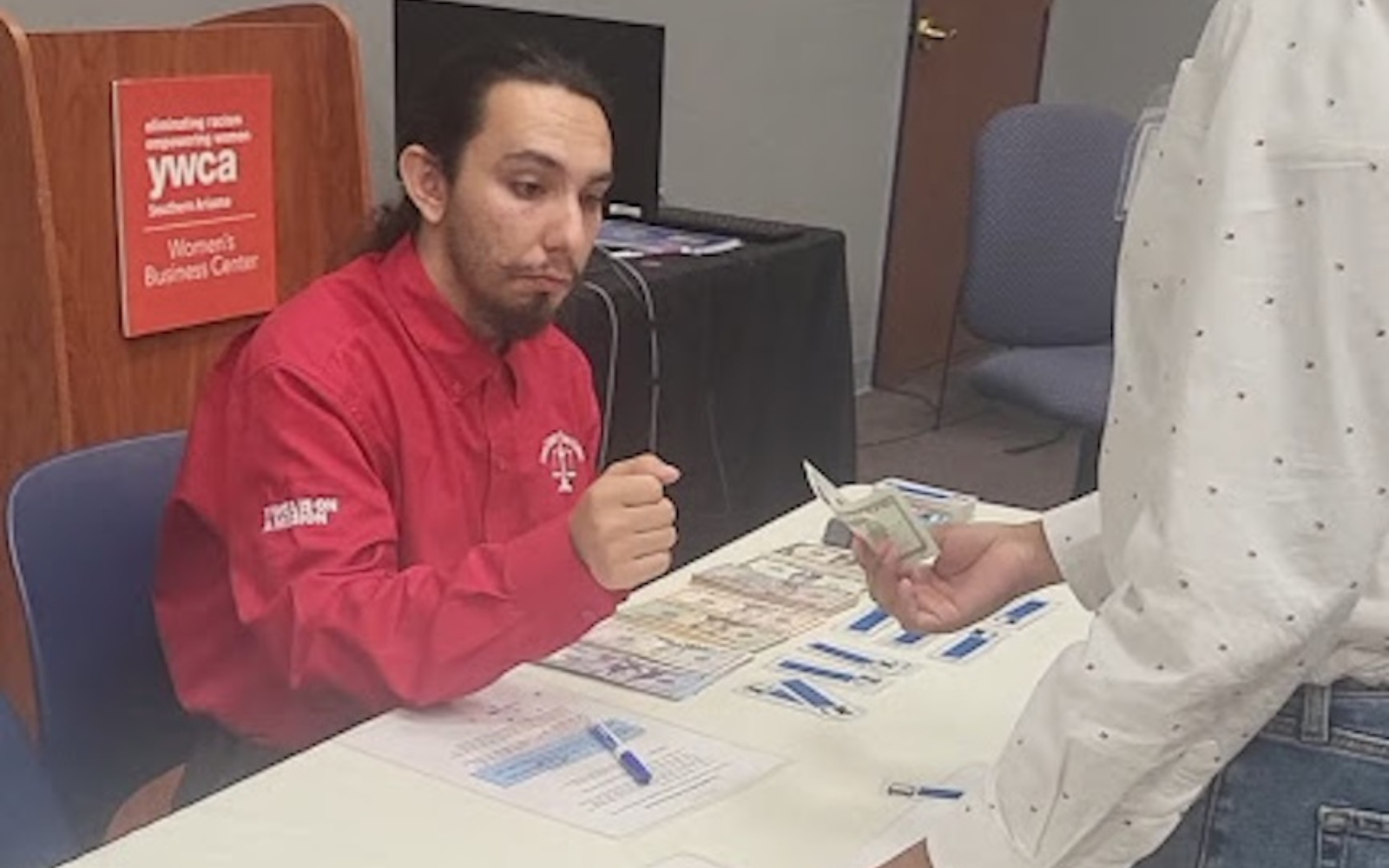

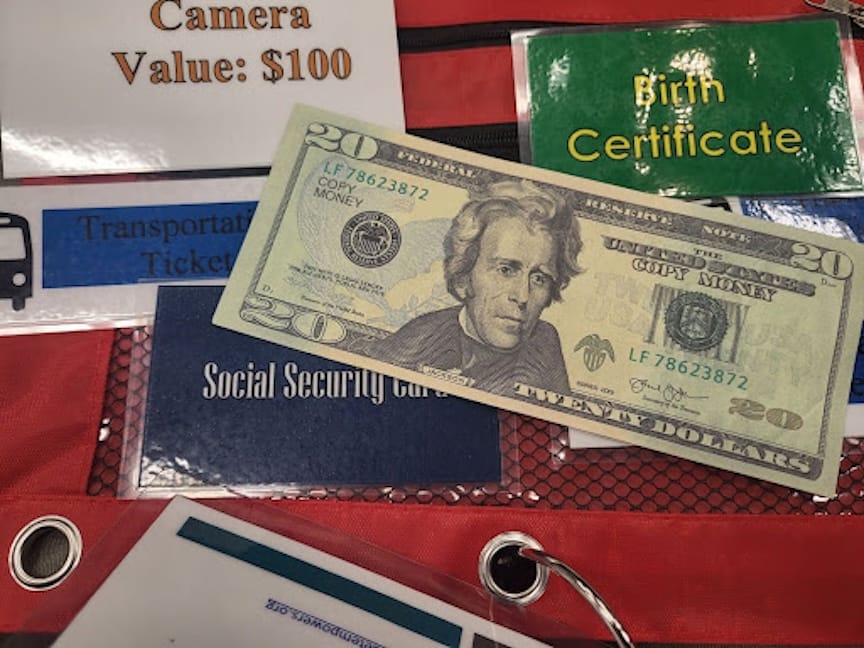

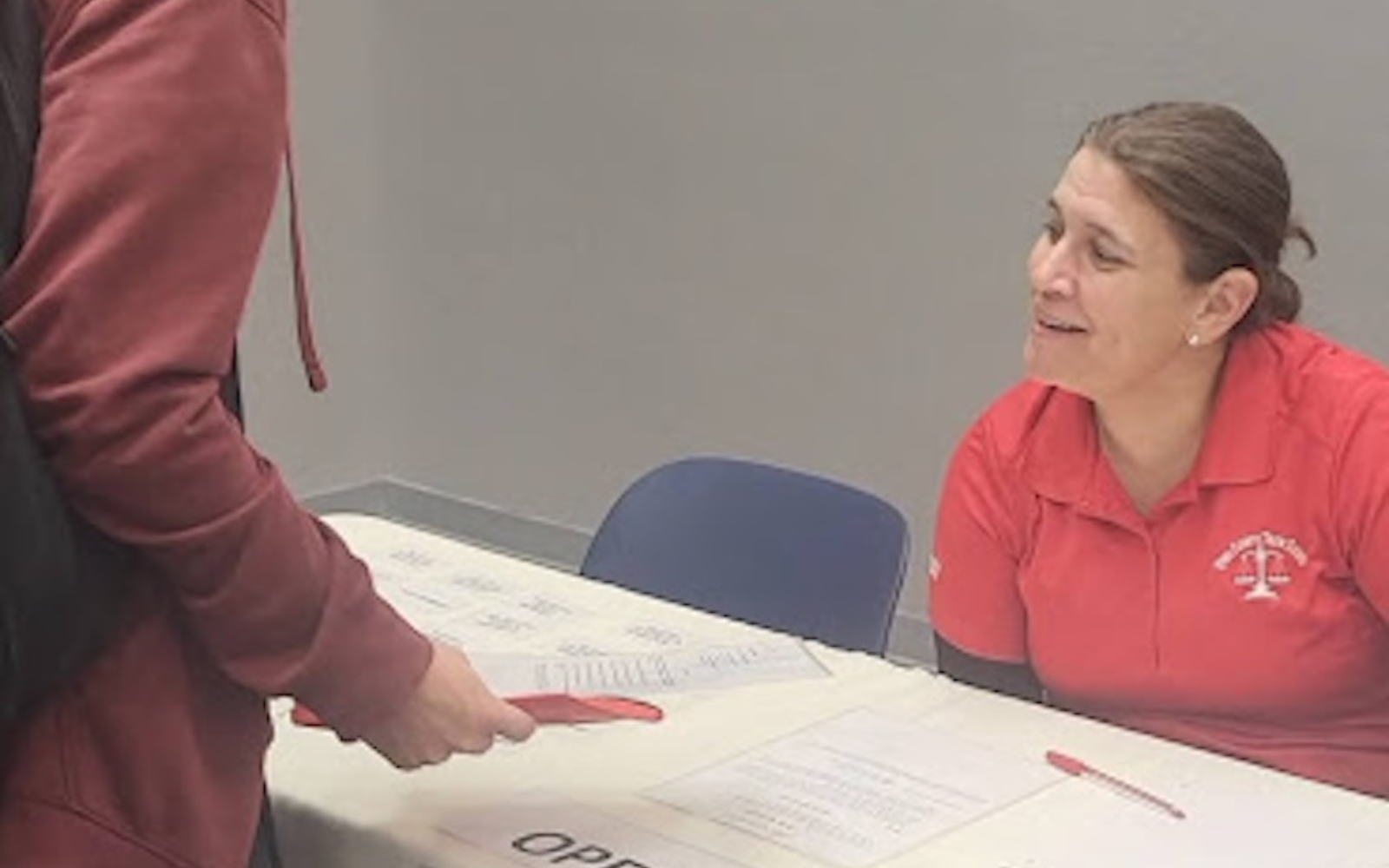

Each participant of the Nov. 22 simulation was given a packet of information containing the name, history and situation of a fictional justice-impacted individual they would be representing. They also had a packet of supplies representing the items, money or documents their person had on hand upon their release from incarceration.

Participants were given a list of tasks, including purchasing food, paying rent and attending probation, but they also had to attend to their personal needs, which means doing what is necessary to earn money to cover all of these expenses. They had 12 minutes to complete all of these tasks each week.

If you value community-powered news, now is the moment to give. Your donation will be matched up to $10,000.

One of the fictional individuals, Scott, was a disabled man who had been incarcerated for 10 years for receipt of stolen property. He was one of the few people lucky enough to have stable housing, as he was living with a girlfriend whom he met while incarcerated through a pen pal program, along with her two children.

Another fictional character, Jayden, had served 15 years for armed robbery and lived in a halfway house.

Like all of the other system-impacted individuals, Scott and Jayden did not start out with the necessary three forms of legal identification to complete their tasks. Scott, for example, had a Social Security card and a birth certificate, but was missing his state ID card.

Without all three forms of identification, none of the stations would allow participants to take any action. This blocks access to employment, banking and social services, among everything else.

Every time a participant visited a station, they were required to hand over a bus ticket or present a bus pass, as none of the fictional people in the simulation had their own means of transportation. This is meant to simulate the public transit system in Phoenix, which does not offer fare-free travel. But even these could not be procured without three forms of ID.

When the clock started for participants to begin the first week of the simulation, they rushed to the station where they would apply to get their missing forms of ID. A long line quickly formed, and when a participant reached the front, they had to hand over a bus ticket for the trip and then request the necessary forms for their missing IDs.

From there, they had to wait in a different line at the neighboring table for one of two pens to become available to fill out their forms and spend $15 in in-simulation currency to acquire the ID.

The line for this took up much of the turn for many participants, and most were unable to get their identification before the turn ended, leaving them unable to purchase food or attend to any of their other necessities.

Both Scott and Jayden were able to get their identifications before the end of the first turn, but were unable to do anything else.

Others were not as lucky and had to return to the identification station at the start of the next turn, simulating a second week. One person who was unable to pay the fees tried and failed to commit armed robbery and landed back in jail.

At the end of the first cycle, after all participants partook in the difficult process to acquire their IDs, they mused during the break about how it could not possibly be this difficult for a formerly incarcerated person to get an ID.

Kim Thomas, a volunteer who helped facilitate the simulation, assured them that it was even more difficult. She shared her story about her release. Her driver’s license had expired while she was incarcerated, so she was instead given an offender identification from the state, which included her name, a photo and Social Security number.

This was meant to serve in lieu of her previous identification but also marked her as a formerly incarcerated individual to anyone who saw it.

The offender ID also did not serve the role the state promised it would. Thomas recalled how she tried to open a bank account upon her release and was turned away from three banks after presenting the offender ID. After finding the repeated rejection disheartening, she used the offender ID to get a library card, which she was able to use as a valid form of identification at another bank.

“In that moment, I was a person,” Thomas said. “Someone saw me, and I mattered.”

Thomas was among the formerly incarcerated individuals who shared her story with a state legislator, which led to passage of a law requiring the state to provide people ending their incarceration sentence with valid documentation.

When the second and third cycles began, participants who were able to complete the ID process in the first turn used their IDs to participate in the other necessary activities, such as attending probation meetings, finding a job or taking care of other legal issues.

At the start of the week, Scott was forced to sell his camera at a pawn shop to get bus money, as the ID application process ate up most of his on-hand cash and bus tickets. The pawn shop refused to pay more than $20 for the $100 camera.

In a stroke of good luck, Scott was eligible for disability benefits — the only one of the multiple applicants for benefits to receive them that week, due to the complicated application process. This provided him with breathing room to purchase his medications, food and bus tickets, pay child support and access his GED documents to help secure a job later.

Jayden was less fortunate, scraping together funds to purchase bus tickets by selling blood plasma. He failed a urine analysis test later that week at probation, which landed him in court and back in the in-simulation jail.

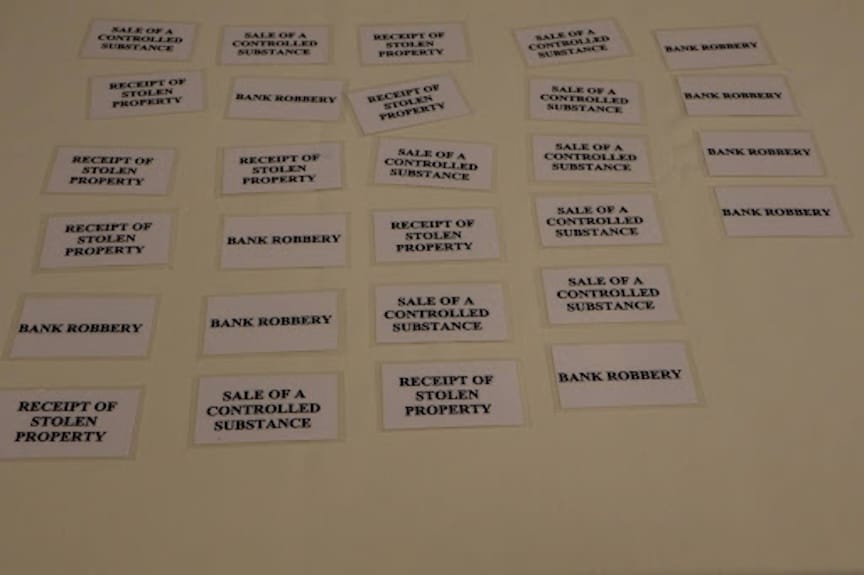

Jayden was one of four participants who ended up back in jail in the second cycle. Participants had the option to go to the chance table at any time, where they could select one of a variety of crimes to commit to earn needed money, with the risk of violating their parole and being caught by law enforcement immediately afterward or at any point in the simulation.

One participant had been arrested for a bank robbery from the previous cycle, another was caught trying to sell drugs, and a third was caught in possession of stolen property but claimed he was merely holding it for a friend.

During these weeks, many participants were given a wild card, simulating sudden life events that might throw off a carefully planned budget or tight schedule already teetering on the edge. The cards could include events such as paying child support or buying new shoes after the old ones were eaten by a dog.

One wild card required a selected participant to carry around a Baby Yoda doll for the week after their babysitter quit. The participant also had to use twice as many bus tickets due to the “additional passenger.”

At the end of the second and third cycles, the process was starting to take a toll on participants, with one telling the group they were “mad as hell.”

Receiving help in the simulation was rare, as the volunteers manning the stations reacted with irritability to participants’ questions. Participants were also reluctant to share their limited resources with one another. One station was an Arouet table providing emergency assistance such as bus tickets or vouchers for parole fees, meant to simulate real-world services. But few participants had the time to make their way there, and fewer still knew about what was offered.

In the fourth and final cycle, many participants had by this point neglected necessities such as food or probation due to time and money constraints.

Scott was one of the luckier fictional members of the simulation and was able to get a full-time job after passing a urine analysis test. But all of his hard work was stalled when his IDs were stolen while he was taking the test, forcing him to start all over again.

At the end of the simulation, facilitators asked the participants if any of them would walk away feeling as if they had won.

Everyone said “no.”

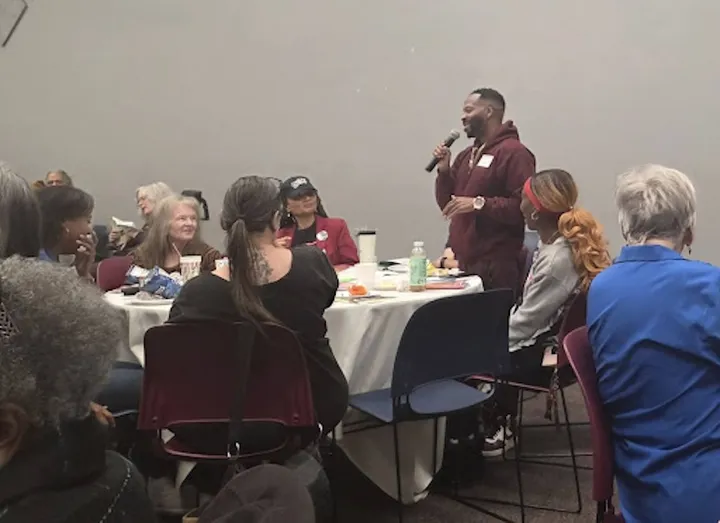

Despite the simulation, Arouet Program Director Brandy Smith believes it is possible to win in real life.

“For me, as a repeat offender, it took putting my sobriety first,” she said. “It takes community, it takes people around you to both encourage you and also tell you ‘you’re being kind of a jerk, so take it down a notch.’ I had to be sick of myself. So it took a long time for me to be where I’m at now.”

Smith said structure is important to Arouet participants, since 33% of the organization’s participants identify as having no family structure.

Charles Pyle, a retired federal magistrate judge and Second Chance Tucson co-founder, participated in the simulation but didn’t find it easy, despite his advanced knowledge of the criminal justice system.

“Even when I was trying to help myself, things didn’t seem to be going right,” Pyle said about his experience.

Pyle believes the simulation was educational and that legislators and probation officers could learn to understand these struggles. He also believes formerly incarcerated people should not be regulated so harshly, but rather trusted to make good decisions and be rewarded for them with things like employment.

Pyle said he believes probation officers are more understanding but are often forced to operate under the orders and expectations of an unsympathetic bureaucracy.

“We need to make things much easier and control people’s lives much less,” Pyle said. “We’re spending too much time and resources controlling every aspect of their lives when we need to be able to get people to independently think, plan and run their lives. We need to be cognizant about the unreasonable demands we’re putting on their time.”

Arouet got the idea for this simulation from the West Virginia Board of Prisons, which had been operating it for 17 years. Arouet tailored it to Phoenix and tied it into the storytelling element of its mission, believing it to be helpful in moving the needle on the problems facing justice-impacted individuals.

“Prison and reentry, if you don’t have to look at it, then you don’t,” Smith said. “This is a great way to educate the public on what reentry is like.”

Ian Stash is a journalism major at the University of Arizona and Tucson Spotlight intern. Contact him at istash@arizona.edu.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please consider supporting our work with a tax-deductible donation.