MOCA exhibit spotlights south side's long fight for clean water

A new MOCA exhibition, “Living with Injury,” honors the south side residents who have spent decades battling TCE contamination and highlights how the environmental crisis continues to affect the community today.

A new exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art is putting South Tucson’s environmental justice movement at the forefront, honoring the residents who have spent decades fighting for clean water and documenting how the contamination that began generations ago continues to shape life on the city’s south side.

“Living with Injury” features work by artists, journalists and researchers and draws inspiration from archival research and local oral history on the impacts of trichloroethylene, or TCE, groundwater contamination.

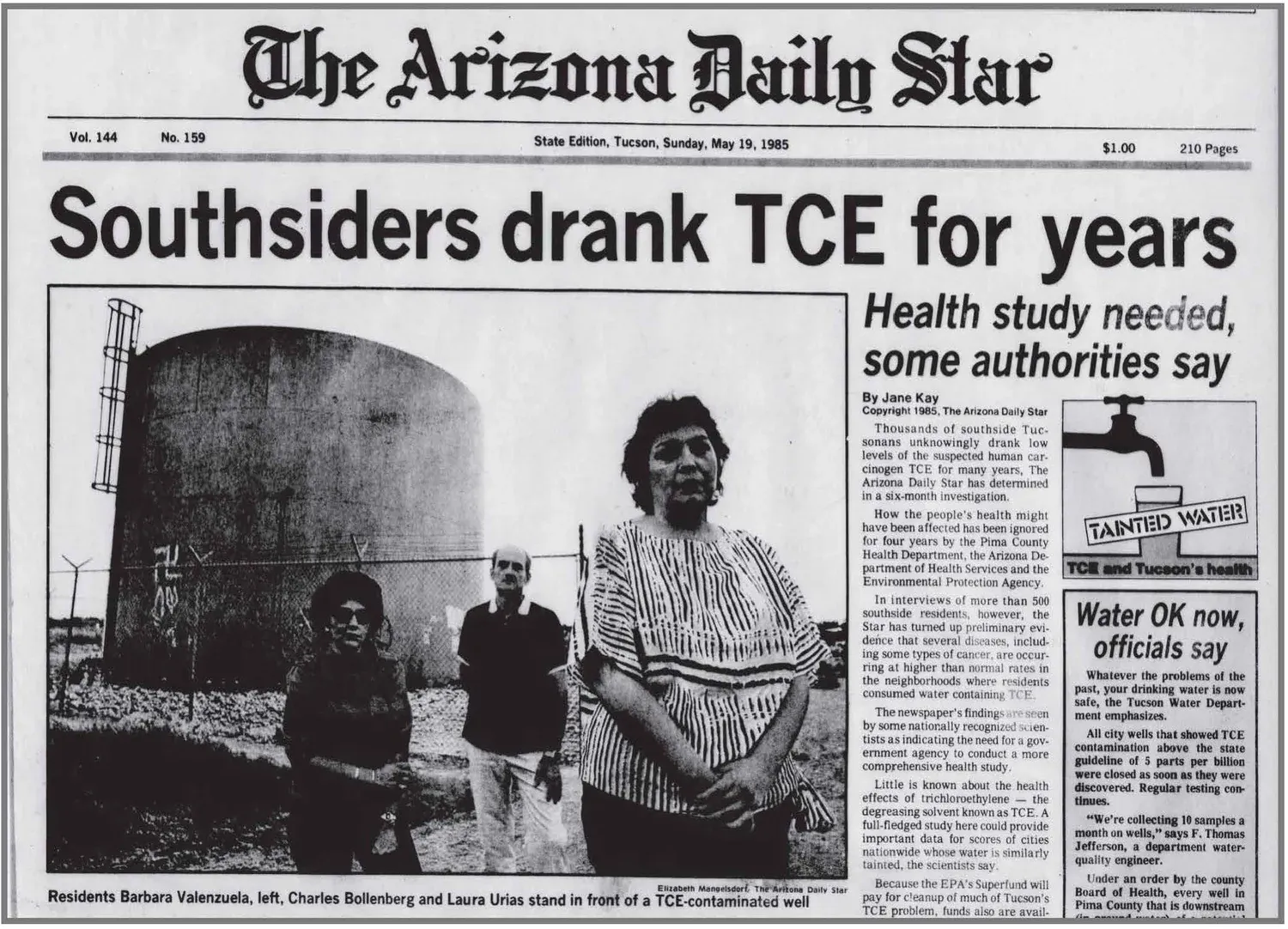

This year marks the 40th anniversary of environmental journalist Jane Kay’s reporting that revealed the extent of the TCE contamination of south side Tucson by Hughes Aircraft Systems, now known as Raytheon.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Hughes Aircraft Company contaminated the groundwater of Tucson’s south side, affecting the health of tens of thousands of residents and resulting in long-term illness and, in severe cases, death. It is one of the nation’s most significant TCE contamination sites.

This year also marks the anniversary of the founding of Tucsonans for a Clean Environment, a grassroots organization that became an advocating force in the fight for social justice, leading one of the earliest environmental justice movements in the country.

“I was born on the south side, I identify as an impacted community member, and spent many years writing, investigating and trying to learn as much as I could about what happened, returned home and ended up writing a book about this,” said Sunaura Taylor, an assistant professor at the University of California Berkeley.

Taylor authored the book "Disabled Ecologies: Lessons from a Wounded Desert," an analysis that explores how disability isn’t only caused by environmental crisis but also actively shapes the resistance to it.

“When I first came back (to Tucson) to do the research, I kind of had this idea of this happened almost 40 years ago, nobody's gonna be really talking about it anymore,” she said. “Then I went to a community advisory board meeting, and it was packed. I was totally shocked by the fact that people were committed to cleaning the water. Then I realized part of the reason is because they never actually got the justice they deserve.”

Taylor co-organized the “Living with Injury” exhibit with Alisha Vasquez, a historian and co-director of the Mexican American Heritage and History Museum.

It was created as part of a larger project, “Survival and Resistance,” that included a series of events to commemorate the south side’s environmental justice movement in response to TCE contamination.

“About four years ago, Sunaura said, ‘I don't want my book to just be stuck in these pages. I want the community who this is about to know this and to know that they mattered,’” Vasquez said. “We chatted about the many different stories regarding TCE and seeing just the harm that was caused is not just a one-time thing of drinking the water and getting sick, but the generational trauma, the generational fear, (and) the poverty that came. Something that theoretically should have ended 40 years ago is still impacting us today.”

While working on “Survival and Resistance,” Vasquez met Dr. Daniel Sullivan, director of the Cultural-Existential Psychology Laboratory at the University of Arizona, who has spent a decade researching the effects of chronic environmental contamination on stress levels.

“Chronic environmental contamination is an extremely stressful experience for some people,” Sullivan said. “We typically think about things like natural disasters as traumatic events that happen quickly, and they can be devastating and people can lose life. But often, events like that are over, but chronic contamination can be an event that lasts the rest of your life. Or perhaps (it) can even be intergenerational.”

In 2020, 73 million Americans lived within 3 miles of a site designated for remediation by the federal government. Stress from potential exposure to a contaminated environment comes with uncertainty, including exposure duration, amount of exposure and whether loved ones are impacted. Over time, this can become an extreme, prolonged stressor.

Sullivan and his team conducted a door-to-door survey of people living in the south side Superfund site, comparing responses to a sample of residents living in another part of town.

“What we found was that specifically people living in southside Tucson, who have lived there since the 1980s when the water contamination occurred, including their descendants, reported the highest levels of cancer, autoimmune disease and birth defects,” he said. “But perhaps most tragically, they also reported very high levels of post traumatic stress specifically related to environmental contamination.”

Of those historically exposed to the site, one in three had clinical findings of post traumatic stress disorder, Sullivan said.

After learning about Sullivan’s research, the City of Tucson’s Human Relations Commission proposed a resolution in September to reaffirm the city’s commitment to addressing groundwater contamination on the south side. The resolution was unanimously adopted, with Sullivan reading it to attendees of the “Living with Injury” opening event.

The event also included a discussion with Lydia Otero and journalist Jane Kay about her experience reporting on the contamination site.

“People had unknowingly been drinking bad water at varying concentrations for 20 years,” Kay said. “It was a 4-square mile area, there were roughly 20,000 people, (and) 4,600 households (affected.) When you think about that, that is so recent.”

From 1979 to 1984, Kay reported on Hughes Aircraft’s attempt to conceal their contamination of the aquifer, alongside the City of Tucson’s lack of response, outside of closing a number of wells.

“It was through that testing period that the first spoiled well was found in 1981, and it was immediately closed. Then there were two more wells closed by 1983, eventually seven wells were closed,” Kay said. “All this was because … Tucson is dependent on one sole aquifer.”

Kay also reported on the Environmental Protection Agency’s designation of Tucson’s Air Force Property 44 as a Superfund site, a polluted location requiring long-term cleanup of hazardous substances.

“Hydrologists who worked for the (EPA) were mapping the movement of the plume. The plume of poison had moved from the Hughes property all the way down to where Michigan Street, south of Ajo,” Kay said. “They were able to tell by what decade the poison had reached wells.”

By 1984, Kay was investigating why a notable number of south side residents had developed serious health conditions.

“There was a woman, Carol Ruse, who was head of the homebound program at (the) Sunnyside school district, and she because she was very concerned about so many illnesses at Sunnyside,” Kay said. “She compiled for me, from 1976 all the way through 1981, all the different illnesses (at Sunnyside) so we could compare that to, say, both had roughly 11,000 populations in their school districts. Sunnyside had four times as many ill people as Amphitheater.”

Kay began talking with people who lived on the south side, quickly establishing concerning patterns.

“People in the Sunnyside school district, Mission Manor, Emory Park, they had been noticing illnesses for decades, and they thought maybe it was the water, because there were incidences of just foul smelling private wells that had been really grossly polluted,” Kay said.

Her series on the TCE contamination included 30 stories that ran over an eight-day period in May 1985. It was later reproduced as a collection of reports sent to 6,000 south side households to broaden awareness of the plume.

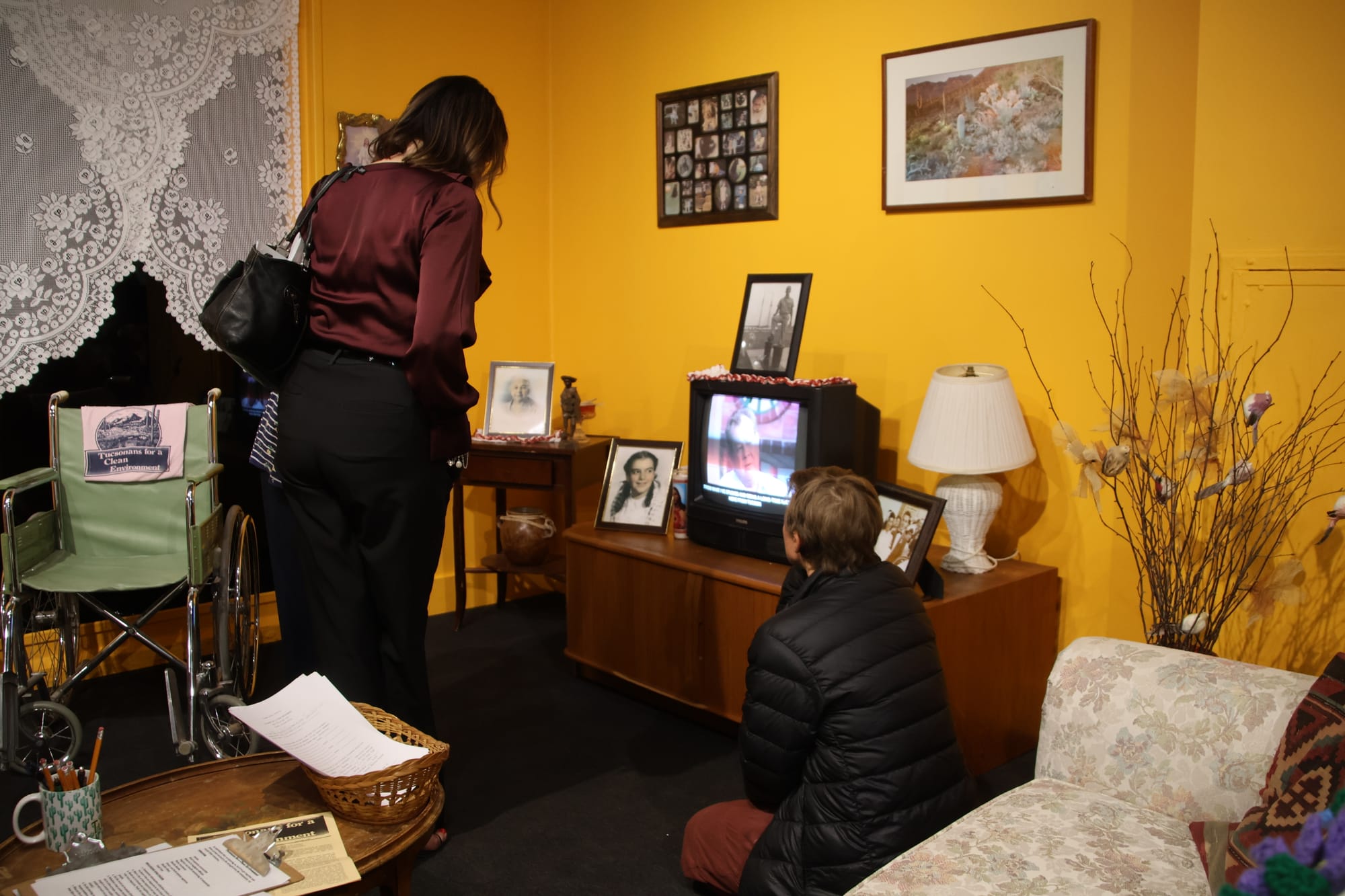

The MOCA exhibit features a full living-room display inspired by Vasquez’s grandparents’ living room, allowing patrons to walk around and explore. Vasquez’s grandfather was exposed to TCE.

The display includes an original copy of the environmental newsletter “Tucsonans for a Clean Environment” and a copy of the Arizona Daily Star with one of Kay’s stories.

Artist Adam Gillen created an image of a fictitious patron saint, Santa Evelina, named for a street near Mission Manor Park where every house had someone who had been diagnosed with or died from cancer — a place residents came to call “the street of death.”

The exhibit will be open to the public until June.

Topacio “Topaz” Servellon is a reporter with Tucson Spotlight. Contact them at topacioserve@gmail.com.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please consider supporting our work with a tax-deductible donation.